CH.06: On Narrative and Form

AKA why I am drawn to subversive work

The audience for narrative-based collectible design is growing—drawing from the art world’s faith in sculptor Walter De Maria’s words: “every good work should have at least ten meanings.” Designers are more focused than ever on imbuing their pieces with layers of storytelling while maintaining a semblance of functionality. Often the barrier to success is there are too many ideas for one to resonate in the final form. Or that an object’s storyline is screaming too loudly to exist anywhere besides a gallery’s white box. I don’t much like work lacking in nuance, but I also don’t like loud bars; people shouting over a glaring soundtrack. I will gladly sacrifice cool for volume control, and I say this because it’s not a ubiquitous opinion (which is an oxymoron anyways).

The best part of living with objects are the faint stories they pick up along the way. Some of that has to do with their creation and some with acquisition—the art deco cabinet I found in a Salvation Army on Cape Cod and loaded into the bed of my Dad’s pickup truck before taking the bus back to Brooklyn. Later that summer, I drove Route 95 back north to retrieve it in a rented cargo van that smelled like fish. I rode with the windows all the way down, hair knotted on my head to keep from blinding me in the wind. But the journey was worth the lives the cabinet has since lived; having seen the interior of five apartments and offered just as many functions along the way. I have a host of pieces with discovery origins like this, hauled up apartment stairs after a Craigslist pick up or uncovered in some reuse warehouse. Many others inherited from a family whose heritage I’m grateful for. But all of these storylines relate to objects which already exist, which have been around for years if not decades. And so, if there are a million cabinets to be found at a million Salvation Armies, why make a new one?

For commercial retailers, the answer is, of course, to make a profit. But small studios and makers don’t operate with a guarantee of breaking even. Is it enough to make a beautiful object or does that object’s existence need to be justified through its meaning, narrative and identity? In our work at the downtown gallery Colony, Jean and I run a residency program that serves as an incubator for emerging design studios. We are unequivocally drawn to designers who have something to say, and we just launched three studios alongside their debut collections: Another.World, MTM Studio and Studio BC Joshua. Because I witnessed each designer’s process for about eight months of collection development, I know how much narrative plays into their creative practices. For Blake of Studio BC Joshua, inspiration was drawn out via the residency’s curriculum—through an ideation process rooted in mood boarding and creative prompts meant to help access what was already very much there. For Max of MTM Studio, the process was more about distilling their threads of multiple narratives into something more focused. And for Youtian and Yingxi of Another.World, we were careful to ensure their collection would find a form as inviting as the world they wished for it to inhabit. (Read more about their work here!)

In writing, narrative can be boiled down to a sequence of events. Earlier this month I heard Ocean Vuong speak about the sequence of his new novel, The Emperor of Gladness, with Jia Tolentino at the heralded Cooper Union venue of literary lore1. He spoke prophetically, silver earring dangling from one ear, about using setting for structure in the book; how the fast food chain, Hall Market, becomes a sonnet—how it offers restrictions to the narrative. And while The Emperor of Gladness more readily deploys plot than his poetry collections or first novel, it still defies the idea of conventional change. In a sonnet, change comes in the form of a volta, the turn of thought or argument that occurs in the poem. Vuong spoke about his wish to write a novel where transformation could occur without change—how it could be gentler. His words had me thinking of how restriction can be generative for designers as well. Form becomes the primary vehicle for their object’s communication—and function offers constraint.

Blake’s Harlem Cottage series represents this well, drawing from the legacy of quiet transformation imbued in the Harlem Renaissance, where creativity reshaped perspectives about community and place. The simplistic cube of his Dogtrot Stool is interrupted by a zig-zag, stair-like cutout at its center. The form was inspired by dogtrot houses, which are Southern cottage style homes split into two by an adjoining, outdoor breezeway or “dogtrot.” One cabin was typically reserved for cooking and dining while the other became a private living space. In the first of the Dogtrot series, Black Cowboy, Blake hand painted laser cut aluminum inlays to showcase African American cowboys on the flat sides of the stool. Ranch culture was a popular styling motif in many cabins but he also recognized that the heroically rebellious legacy of cowboys has been romanticized throughout pop culture as being solely white. Black Cowboy reinterprets the hero in the context of cottage culture—all within the confines of its square silhouette.

Looking at the Dogtrot Stools in person without companion text, you’d be forgiven for not grasping every storyline they contain. You would likely still find their structure striking, their function highly efficient. This is a marker of a successful furniture object: It can stand alone, form forward and context aside. It contains and conveys meaning without raising its voice. If the stool couldn’t stand alone, or in the concert of a home, then it would be at risk for crossing back into the art world. I am interested in work which toes the line, or connects the dots as PIN-UP's latest issue puts it. But I can also attest that the gatekeepers to the design world are very much reliant on the one traditional thing which separates design from art: FUNCTION. It’s a boring word and doesn’t do justice to the poeticism instilled in objects meant for daily use. A home is meant to be lived in, its furniture is meant to be used. I want to sit in my chair, not just look at it.

When an interior designer is sourcing stools for a client’s home (likely after seeing a photo online), I imagine they will include one of Blake’s for their solidity, for the pop of hand-painted color against the warmth of walnut. In that sense, the Dogtrot narrative becomes subversive; the stool offers a place to sit and its user an invitation to learn from the history it calls upon. Much like literature, furniture objects have the power to convey meaning to those who were first charmed by their aesthetic beauty and then called to question a belief / challenge their opinion / open themselves to an angle outside their own. As the writer Deborah Levy put it, “All narrative is a Trojan Horse. What is hiding in its belly and what is hiding in its mouth?”2 Make the stool gorgeous and then you can fit a lot of meaning in its belly. Make it functional, too, so that the studio can sustain itself by actually selling it. The stories of objects, and of their makers, are inherently political. I want more diverse voices and I want their practices to be sustainable.

While I try to remain wary of the working class chip on my shoulder, maybe some part of my distaste in loud work—chaotic, messy, underdeveloped, alienating—is rooted in anxiety of whether or not it can find a buyer to support it. Or rooted in a preconception that only the privileged can make work without considering their audience. But then I think of Vuong’s constraint and Levy’s Trojan Horse and how maybe I’m drawn to quieter work because I really do believe in the subversive power of beauty. Although reading it to myself written out like that—subversive power of beauty—it sounds too neat. A little too pretentious. My aesthetics leanings might be best chalked up to my personal inclination for nuance and nothing more. Like how I revisit the smallest memories of childhood most often—Nancy Drew pages flipped from underneath the garden ferns, the flat sting of beach grass caught between my palms. These days, the moments I find most reaffirming are still the quiet ones: The flood of light passing through a wine glass on a balcony or the flick of a snail curling back within its shell. An open window on a late night drive; that extra breath over dirty dishes.

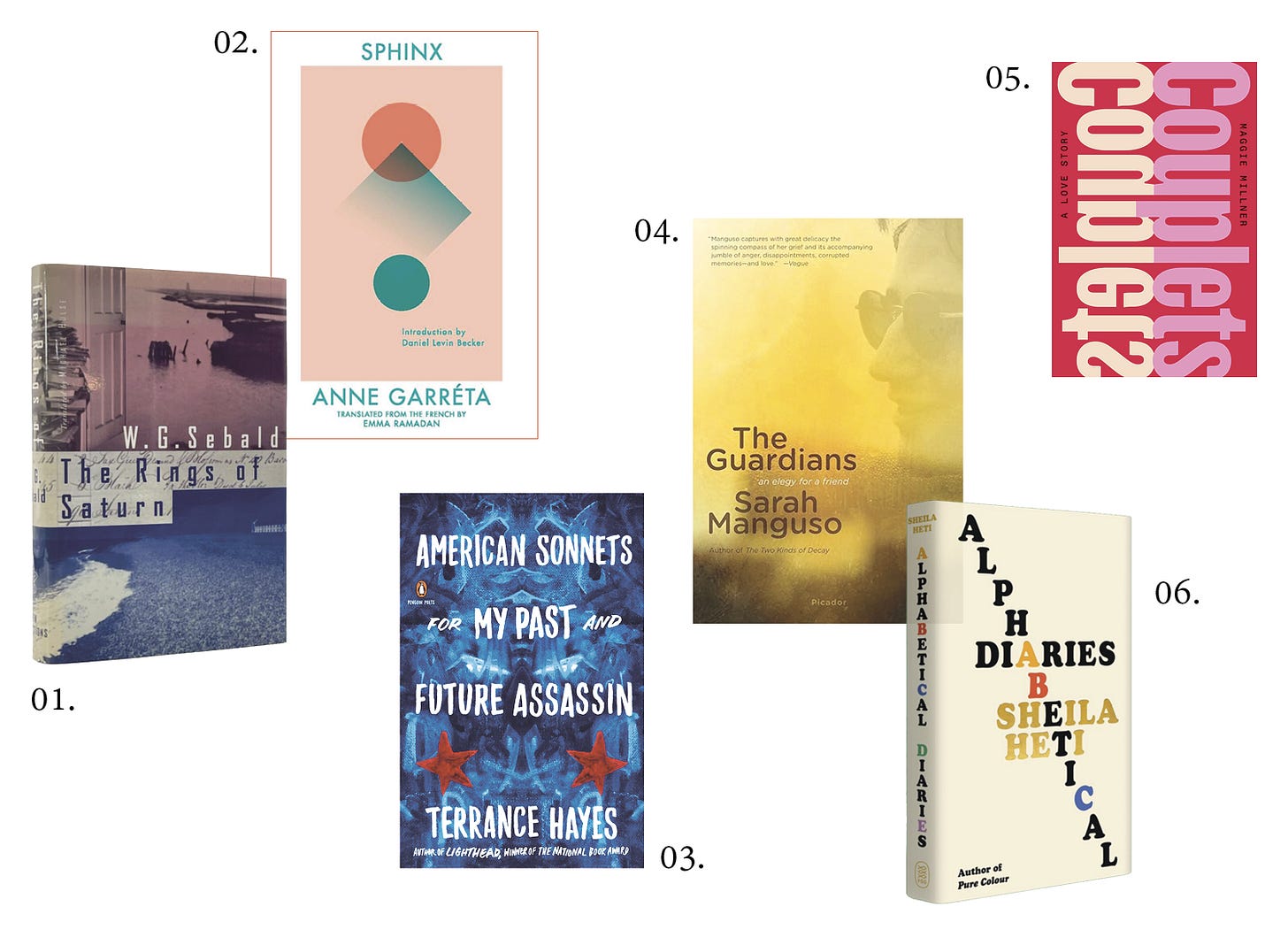

SUGGESTED READING: FROM POETRY TO OULIPO

Each of these recommendations are anchored by a commitment to their form and its constraints. Think of them as objects in and of themselves.

01.The Rings of Saturn, W.G. Sebald // A 1995 novel where the narrative arc is a first-person account of a walking tour of Suffolk, England. Sebald uses the structure of the walking tour to prompt places, people and memories encountered along the way. (Sidenote—this is only one of multiple books I’d like to read on walking. I might write about why after I’ve read them all).

02.Sphinx, Anne Garréta // Founded in 1960, Oulipo is an experimental French literary movement based on constraint. Garréta, one of the only female members, was also the first person born after its founding to be admitted to the movement. I don’t really know what that admittance entails, but I do know it sounds silly. If you want to know more about this novel’s constraints, I suggest reading this technical reviewe. TLDR; it has to do with the absence of gender.

03.American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, Terrance Hayes // Seventy sonnets bearing the same title, this collection was written in the first two hundred days of Trump’s 2016 presidency. Hayes is brilliant: It doesn’t matter if you’ve never read poetry before, read this immediately.

04.The Guardians: An Elegy for a Friend, Sarah Manguso // This is a beautiful, slim memoir memorializing Manguso’s friend in the form of an elegy. She is one of my very favorite authors.

05.Couplets, Maggie Milner // How in the world did Milner make something so seemingly cliché (the couplet—two lines of rhyming verse) so devastatingly cool and seductive? I originally loaned Couplets from the library, but I'm going to purchase a copy because I already want to reread it.

06.Alphabetical Diaries, Sheila Heti // Heti took a decade’s worth of her diaries and entered each sentence into an alphabetized spreadsheet. Then she edited and cut until what was left was this weirdly compelling record. It’s incredible how strong the narrative threads remain when chronology becomes dictated by alphabetical order instead of sequential time.

Ocean Vuong. “The Emperor of Gladness.” Penguin Press, 2025.

Deborah Levy. “The Position of Spoons: And Other Intimacies.” Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024.

Couplets, it slays me. The moment I read a page and turn to the next one, I go instantly back and start again.

I just picked up that Anne Garréta book! And her book In Concrete. Motivation to put them towards the top of the pile. Also, have you read The Carrier Bag theory of fiction? That Deborah Levy quote made me think about it